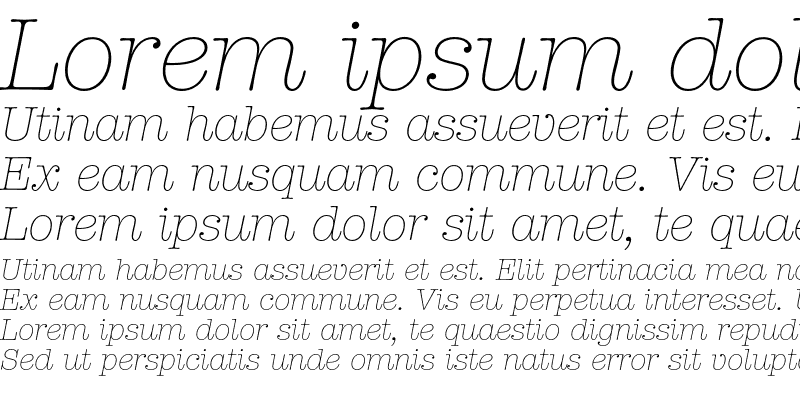

The past is robbed of its authenticity and historical context. The problem with the nostalgic vernacular is that it steals from the past to deny the future. As explained by Jeffery Keedy in Lift and Separate: Graphic Design and the "Vernacular" (the slim book with the famous velour cover), “The most familiar ‘use’ of vernacular is to reproduce nostalgia. The term “vernacular” is almost pejorative, and with good reason. For better or worse, most monospaced faces are vernacular fonts – type that immediately conjures an image or feeling of time and place. Monospaced fonts come in so many variations that the feeling they impart varies all over the map: immediacy, intrigue, corrosion, officialdom, simplicity, antisepsis.

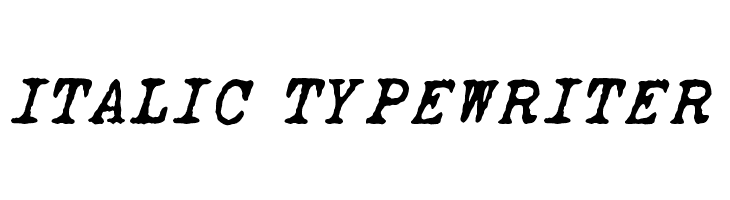

If "good" type is like a well-tailored suit that you barely even notice, in too many cases monospaced fonts are the flower on the lapel that squirts water in your eye. Just as derivative graphic designers in the 1980s cloned Neville Brody’s typographic esthetic, doing so again in the ’90s with David Carson’s grungy designs, it seems that many designers are using monospaced fonts without always considering their suitability for the job. Typewriters were invented because handwriting can be illegible the standardized look of typewritten text connoted professionalism. (“I don’t like this font – I get it.”)Īllied with this pretense is the artifice of using typewriter fonts as a means of signalling ironic computer metaliteracy to other designers: “Macintosh computers let me use any font I wish, and I, a free-thinker, elect to make a 1984-like statement decrying mechanization and the dehumanization of modern technology by using the prototypical fonts of mechanization and dehumanization.” In particular, anyone who uses Courier – the prototypical typewriter font – is playing with fire given its vernacular among designers: it’s the font your printer spits out when it can’t find the right font. These days, hip club kids with disposable incomes have taken to wearing bowling shirts emblazoned with names like Ray or Mavis (often the real thing in genuine polyester, bought from thrift shops and the like), doing so with a kind of retro hipness that says “I don’t like this shirt – I get it.”īy the same token, well- educated designers with degrees from prestigious institutions (or, worse, with no qualifications other than owning a Macintosh) are using state-of-the-art desktop publishing tools to produce layouts using typefaces that wage slaves two generations ago, most of them female, stared at day after day in the typing pool. To be a bit more precise, the vogue isn’t merely for fonts that look like they came from a typewriter rather, it seems that any monospaced or fixed-pitch or uniformly-spaced font, where each and every character occupies the same width, is all the rage.īut there’s more to this trend than designers simply “liking the look.” Typewriter fonts are nostalgic: The first type ever manipulated by many designers now in their thirties or older was found on the dusty old typewriter in mom’s attic.

These days, hundreds of graphic designers are using computers to set type using faces similar to those their grandmothers were stuck using in their 9-to-5 office work: typewriter fonts. That was a few years ago now and, as usual, it seems Madonna was ahead of the curve. Take a look at the liner notes and you’ll find a disclaimer reading “Notice: All surface noise on the song ‘Erotica’ has been included intentionally.” The most powerful woman in pop music opts to use a new technology to replicate the defects of an old one. Slip Madonna’s Erotica into your high-tech CD player and the first thing you hear is the all-but-forgotten sound of a phonograph needle scratching its way around the outside of a vinyl LP. (Sidebars on Lucida Typewriter, Trixie, Courier, American Typewriter) Monomania With thousands of typefaces at their fingertips, just why are designers opting for typewriter fonts?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)